by Vincent Giordano

The bitter history between Myanmar (formerly known as Burma) and Thailand (formerly known as Siam) began on ancient battlefields. This included 24 wars between Ayutthaya (the ancient capital of Thailand that flourished from the 14th-18th centuries) and Myanmar that were fought by the nation’s most powerful armies.

In 1767, after a 14-month siege, Ayutthaya fell to the Burmese and was totally destroyed and burned to the ground. The king fled, and the Ayutthaya kingdom came to an end. It was this defeat, and the huge damage that the Burmese victors inflicted on the Thais, that has remained etched in their memory ever since.

Following the indiscriminate slaughter by the Burmese, tens of thousands of prisoners were led away to Burma in captivity. Among these captives was a young, skilled fighter named Nai Khanom Tom. Nai was born in 1750 and became an orphan at only 10 years old, when both of his parents died. He was then taken to live in a nearby Thai monastery, where he supposedly learned how to fight.

King Hsinbyushin (known in Thailand as “King Mangra”) was one of the most famous kings in Burmese history and was known for his victories over the Chinese and Thais. He traveled to Rangoon to preside over the Shwedagon Pagoda Festival in 1775. For the early Burmese and Thais, participation in festivals, rituals, and feasts was an important social obligation for the people. Royal and religious festivals provided an opportunity for the king to display himself to his people.

Festivals at the time included many important religious ceremonies, along with all forms of entertainment, including boxing and wrestling.

Lieutenant General Albert Fytche, who served as Chief Commissioner for the British Crown Colony of Burma, shared his observations in his 1878 book, Burma Past and Present:

“On holidays or festive occasions, the most common diversions are boxing and wrestling. Ground for the ring is prepared and made soft with moistened sand, and around it, the spectators sit or stand, a scaffolding being erected on one side for the umpires and ‘heads of the people’. As is the practice at every festival, a band of music is in attendance and plays during the combats.”

King Hsinbyushin decided during the festival to have one of his Thai captives fight against a Burmese boxer to see who was superior. Nai Khanom Tom was selected to participate against the king’s chosen fighter. This type of escalated combat was the product of a unique environment that could at times mirror that of ancient Rome, where Roman gladiators who were either prisoners of war or criminals sentenced to death were selected to fight in brutal matches.

Even in Thailand at the time, these type of contests during festivals were common, as shown in James Low’s article, “On Siamese Literature”, which was drafted in 1829, revised in 1836, and finally published in Asiatic Researches vol. XX pt. 11 in 1839:

“Len Chok Moei (or boxing matches) are common at all great festivals and entertainments. There are no set number of rounds. The king if present — or if he is not, one of his courtiers regulates the barbarous sport and rewards the victors…”

Prior to the start of the match, Nai Khanom Tom performed his Wai Kru/Ram Muay, which is a Thai pre-fight ritual dance, the central purpose of which is to pay respect to one’s teachers, parents and ancestors (a Wai Kru) and to make a highly stylized threat to one’s opponent. In ancient times, when boxers fought in front of royalty, the Ram Muay also paid respect to the king. It is different from the opening Lethwei Yei, which the Burmese fighters use before their matches.

The Burmese, being extremely superstitious, believed the movements were a form of black magic. Despite knocking out his opponent, Nai Khanom Tom was not awarded the victory because the Burmese ruled that the opponent was distracted by the dance.

The king then asked if Nai Khanom Tom was willing to face nine more Burmese fighters in succession to prove his fighting ability. Nai agreed and was luckily able to fight off all nine opponents (if it was indeed nine opponents or far fewer). The Burmese have a deep-rooted belief in numerology, and numbers have religious, political, and magical meaning. Nine is an auspicious number to them.

King Hsinbyushin was so impressed with Nai Khanom Tom’s fighting ability that he allegedly remarked, “Every part of the Siamese is blessed with venom. Even with his bare hands, he can fell nine or 10 opponents. But his Lord was incompetent and lost the country to the enemy. If he had been any good, there was no way the City of Ayutthaya would ever have fallen.”

The king then granted Nai Khanom Tom his freedom, along with the choice of either money or two beautiful Burmese wives. Without hesitation, Nai Khanom Tom said he would take the wives, because money was easier to find. King Hsinbyushin then awarded him two Burmese women from the Mon tribe. Soon after, Nai Khanom Tom left Burma a free man, taking his wives back with him to Thailand.

The legend of Nai Khanom Tom has become Thai folklore and has been used as an emblem of Thai strength in the face of Burma’s brutal tyranny. The story was originally drawn from several lines in a Burmese chronicle that was discovered in the 19th century and embellished over time in Thailand. To the Burmese, Nai Khanom Tom was a Thai who fought bravely when his life was on the line and showed great skill after the brutal defeat of the Thai people by the Burmese in Ayutthaya. To the Thais, it demonstrates that the ancient practice of Muay was already formidable and has been practiced for as long as any Burmese martial arts practice.

This clear embellishment of a simple story demonstrates how the Thais try to keep their martial arts tradition closely identified with Thai culture and history, as noted scholar Peter Vail points out:

“The important point about popular stories which conflate muai thai with martial arts and battle techniques generally is that they thereby conflate muai thai with notions of a Thai warrior spirit, cakravartin kingship, war, and later with ideas of a nation associated with these same elements. It also establishes for boxing a deeper and more important sense of past by projecting muai thai back into seminal episodes in Thai history.”

One of the most-cited stories in the Thai-Burmese relationship happened between two formidable opponents, King Naresuan the Great (1555-1605) and King Bayinnaung (1516-1581), who assembled the largest empire in the history of Southeast Asia during his 30-year reign.

When the future Thai King Naresuan was seven years old, the Burmese (who then controlled Ayutthaya, having conquered it in war) took Naresuan captive to Burma. This was to ensure that Naresuan’s father (then a prince) would remain loyal to the Burmese. Naresuan was raised to the title of prince by King Bayinnaung and was educated in military strategy, martial arts, and political science during his years as a captive at the Burmese royal court at Pegu.

Prince Naresuan returned to Thailand when he was 16 and immediately committed his life to nonstop warfare. It was said that he didn’t just defend Ayutthaya; he actively attacked Burma. 19 years later, he became the King of Thailand and one of the most revered monarchs, continuing his military campaigns until he died at the age of 50.

Naresuan used his extensive understanding of Burmese war tactics and strategies to craft a unique, diverse, and reformulated Thai fighting system that led to Burma’s eventual downfall. His memorable battle with the Burmese Crown Prince Maha Uparaja, heir apparent to the Burmese empire, in an elephant-back duel remains an indelible image of Thai fighting ability — though how Maha Uparaja came to meet his demise is disputed in Burmese chronicles, and many other chronicles of the time.

The disputes over the origin of the martial arts systems has long been a growing point of contention between the two countries. The recent revival of Lethwei has brought the origin stories back to the forefront. This follows a similar pattern employed by the Cambodians when they resurrected Pradal Serey, introducing the same rhetoric employed now by the Burmese. Cambodian Moul Vongs reported in 2001:

“…there is a concern among some, such as the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts, that Khmers do not realize that this sport originated here and that, although similar to the Thai sport of Muay Thai, it is intrinsically Khmer, down to the carved images of ancient boxers immortalized in bas-relief on the walls of Angkor temples. Khmer boxers have in the past refused to attend bouts in Thailand called ‘Muay Thai tournaments’…”

Any debt owed to the Khmer empire is certainly there, but it’s in the very old bare-knuckle and weapons systems and not so much in the modern ring system of Muay Thai. In Thailand, there are many regional styles that are very distinct, and they definitely drew from influences and countries outside of their own. The Korat Thai system that I learned looks very similar to the old Khmer system that I learned when I was very young, and then again as an adult in Cambodia. Instead of drawing on serious research to link it back to the specific regional bare-knuckle systems (and older weapons that match closely through history), spiritual practices, and physical movement, they attempt to attach to Muay Thai, the most popular modern form, which is a diversion from the past for the Thais. Even the old Thai fighters felt there was an enormous divide between the older bare-knuckle/bound-fist fighting and modern ring Muay Thai:

“Talking to a number of the old boxing teachers, some of them in their 80s and still seen at the ringside, one inevitably has to listen to their favorite topic, the decline of Muay Thai.

We had to fight the little guys as well as the big ones and had to know all the tricks of the trade. We used techniques that today’s boxers have never heard of. Commercialism has destroyed the art.”

I can love, respect, teach and train Thai, Cambodian, and Burmese systems — as I do and have done for decades — without being too deeply drawn into their battles of nationalism and warped histories. Even as I clearly tied the influences of ancient Indian systems to those of Burmese Lethwei and Naban through their practices like Lekka Moun, it fell on deaf ears. This was a clear sign that there was no interest in conducting hard research on the past — even though it would answer their questions on what they are practicing, and the clear influences this has had on them.

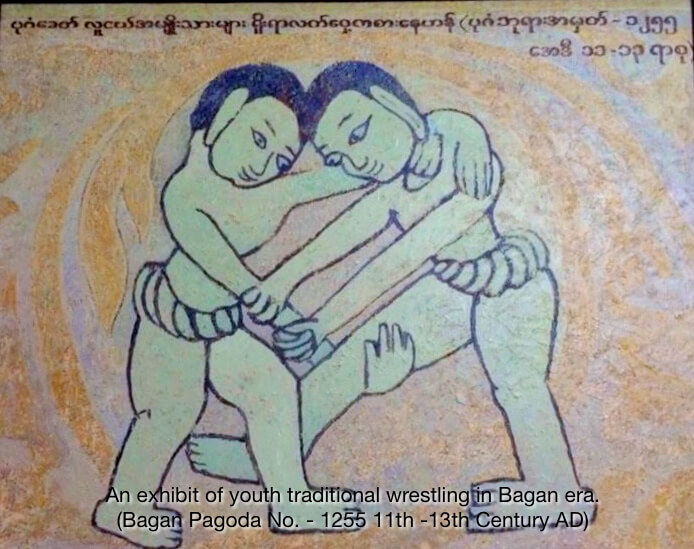

In the Myanmar Letwhay Association’s booklet, Myanmar Letwhay – The Historical and Original Art, which they used to promote their major fight card in Yangon, it states:

“Evidences have been found that Myanmar Letwhay has existed even since the Age of Bagan (roughly between 11 AD and 13 AD). Researchers — including expatriates — agree that some paintings found on the ancient pagodas in Bagan are references to Myanmar Letwhay techniques.”

The painting they reference and use for the cover of the booklet is clearly of Naban (Burmese wrestling), as evidenced by the actual notations above the mural. Lethwei practitioners, and many other modern Burmese masters and practitioners, rarely speak of Naban, and for the most part, don’t want it included in their promotional conversations. Wrestling is one of the oldest martial sports practiced throughout the world and has a deep cultural history within Myanmar.

The paintings prove important martial arts history, just as the murals in Ayutthaya probably did before the wanton destruction by the Burmese. The three ancient arts — bare-handed fighting, wrestling, and weapons training and fighting — were all practiced concurrently throughout Southeast Asia and were often tested cross-culturally in both war and sporting engagements.

The Myanmar Martial Art Federation in their historical overview outlines the early beginnings of their art:

“The records say Myanmar arts of self-defense have been in existence since the 8th Century A.D. The first Myanmar Empire was founded by King Anawratha in 1044. The “Pwe Kyaung Sayas” of Bagan Era before King Anawratha’s reign had gained influencing power among people of that time by relying on their skillfulness in martial art.”

The Burmese have claimed that Lethwei (or an earlier incarnation of the art) became popular and widespread during the reign of King Anawratha (1044-1077).

In their article, “If He Bleeds, Stop Hitting Him”, which appears in Black Belt magazine’s November 1974 issue, the authors Myo Thant and Ba Nyein offer:

“Although the exact origin cannot be traced, it was known that Ayegyi monks during the reign of King Anawratha were skilled in Myanma Letwhei, as well as horse riding, fencing and stick fighting. Descendants of these monks taught princes, sons of noblemen, and military personnel as part of the Gasar Khunin Kyaung (Seven Schools of Arts). During their leisure, the soldiers and warriors had engaged in Myanma Letwhei. Distinguished boxers were praised by the king. In fact, when the country lacked a regular army, the Letwhei boxers were chosen to defend Burma.”

In the chapter, “Traditional Burmese Boxing”, from We the Burmese: Voices from Burma by Helen G. Trager, it also states:

“According to the historians, boxing was taught as a compulsory subject to the Burmese warriors during the reign of Uzana I of Pinya, in 1323 (possibly 1325, since Uzana reigned from 1325-1340). Up to the time of King Thibaw (1878-85), the last Burmese king, Burmese warriors skilled in the art of boxing were designated ‘royal boxers’, and their names were carried on the treasury roles.”

Alex Tsui, a Muay Thai researcher and teacher, offers his views on the Thai-Burmese conflict over origin in his early writings on the subject:

“These assumptions for the Burmese are marginally reliable at best. It is probably true that both had undergone training in fighting arts, while staying involuntarily in Burma; yet, given the situation as it was in the Ayutthaya period, Naresuan — regardless of [being held hostage for] 10 years in Hongsawady until age 15 — would be a superior warrior in any event, and Nai Khanom Tom was by all accounts a trained Muay fighter at the time he was captured. Further, one cannot ignore the fact that among the early Thai tribes that settled in northern Thailand were many great warriors.

It is a matter of historical reality that boxing (Muay), [whether] in primitive or lethargic form, was in the Thai tribes well before they entered the Menam River basin. It had continued to be practiced and was subject to refinement as the Thai ethnic groups moved on through the ensuing Yonok, Haripunchai, Lanna, and Sukhothai periods. By the year 1350 AD, it was already [a] well-defined native sport and [part of] popular culture in the Kingdom of Siam.

While the Burmese case may further rely on some 11th century engraved relics of a boxing scene on terracotta tiles [from] the Mon period found in the northeast area of Pegu, the Thais have uncovered artifacts (images of pugilists) dating back [to the] 8th-10th centuries in the Haripunchai period. Even though it may be open to debate that the origin of this latter discovery could well be a Mon-Khmer source, it nevertheless is beyond dispute that unarmed combat art of a kind was actually being practiced in northern Thailand, even in those early times.”

The actual evolution of the two bare-knuckle arts follow different trajectories. This has led to many misunderstandings, especially from the Burmese side, of what Thai ancient bare-knuckle/bound-fist boxing is, and what Muay Thai is.

The original Thai bare-knuckle form had no rules and used every tactic, including headbutts, throws, and anything the fighters could bring functionally into the arena. There were no hand wraps. There were no weight classes.

The Ancient Thai Fighting Art is an old text that was recopied in March 1923 from an original source, it clearly shows in the Sixteen Boxing Strategies the headbutt attacks in the Thai arsenal:

“Head Attacks:

- Left sided buffalo gore;

- Right sided buffalo gore; and

- Buffalo smash forward frontal”

I went through the many techniques and tactics contained and described in the ancient text that I translated with the assistance of several of the older Thai bare-knuckle teachers and most of them knew how to use and teach these old tactics.

Old-style Thai fighters initially fought bare-knuckle, then horsehide straps or thongs were used to protect the hands and wrists. This was later changed to cotton yarn or hemp of varying textures that could be knotted to inflict maximum damage. This led to this type of fighting being called “Muay Kaad Chuek” (fighting with wrapped hands, or “rope-bound boxing”). The wrapped hands could additionally be dipped in tar, starch, or tree sap to harden them, but it seems this practice was not the norm; rather, it was used for isolated grudge matches or to up the notch in a popular contest.

There were some exceptions to this, as Vallabhis Sodprasert recounts from his discussions with his teacher:

“The old Muay (known as ‘rope-bound boxing’) did not always have contestants binding their hands in fights across all regions … the Muay style that Master Khet saw, which used no fist-binding, was Muay Lampang and Muay Thai Yai (or Shan) because they used their hands to grab, push, or yank the tendons in order to sprain or for lethal effect.”

This type of fighting, like its previous incarnation, resulted in many casualties — some severe, as Hardy Stockman points out:

“A bout lasted as long as a fighter could continue. Many a boxer is said to have left the arena on a bamboo stretcher, dead.

By the beginning of this century, Muay Thai was taught in schools. It continued thusly until 1921, when too many serious injuries and several cases of brain damage prompted the government to prohibit the practice in all elementary and high schools. The use of hemp ropes and seashells continued until the 1930s. At that point, Muay Thai underwent a major transformation. A number of rules and regulations from international boxing were adopted, modern boxing gloves were introduced, and the shell was replaced by a metal cup as a groin protector. Weight divisions were established, and bouts were staged in a modern ring.

According to some old-timers, it meant the death of Muay Thai, and the birth of a new sport.”

The modernization of Muay Thai began a new evolution that continued to draw from Western boxing through the teachings of the British, combined with Westernized rules of sportsmanship. This did not develop suddenly, but rather slowly over time. These sweeping reforms had more to do with what was happening within the country than just the idea of modernizing an ancient sport.

This slow progression molded a new fighting sport, which over decades began to develop and take on a distinct fighting style. Special equipment was developed, from Thai pads to unique Thai shorts. Camps were designed and developed to house fighters who could live and train full time. Neighboring countries (like Burma, Cambodia, and Laos) continued the old style, resisting change and Westernized influences. Cambodia and Laos, copying from the success of Muay Thai, made the transition to a modern form some decades later, while Lethwei resisted change but still integrated some of the Western influences and drew on ideas from the still-developing Muay Thai to minimally modernize the sport.

Lethwei assumed a high level of prestige in earlier times. Much like Muay, it was taught to military personnel and in the royal court to princes and noblemen.

In these earlier times, during the golden era of Lethwei, lavish fight tournaments saw winners awarded large sums of money, as well as highly valued horses. Lethwei tournaments were often held during pagoda festivals, monks’ funerals, and other holidays and special events. The largest of these rural tournaments were traditionally fought once a year for the various pagoda festivals and during the extended Thingyan New Year holiday festivities.

In the Colonial period that began after the British invasion in 1885, Burmese boxing went into serious decline. It was embargoed, oppressed, looked down upon, and used primarily as entertainment for British officials and the rich. It remained an active sport in the rural villages, where it was quietly propagated and kept alive — despite British suppression that saw Burmese boxers classified as “vagrants” and “habitual criminal offenders” who were subject to arrest.

During this period in the Kayin and Mon states, farmers staged traditional nightly Lethwei matches around massive bonfires as tribute to the Goddess of Rice in the hopes that she would bless their crops during harvest time. These older tournaments also emphasized the importance of music and songs, which accompanied each bout. The prizes were also grander during this period, with highly valued gold and diamonds awarded to the winners.

The eruption of World War II and the Japanese invasion brought the country to its knees. The Japanese-Burmese Budo Association attempted to restore the ancient Burmese martial arts systems under Japanese supervision and control. Old Burmese masters from various regions were brought into the open to exchange knowledge and techniques. This resulted in some forms of the ancient systems being revived and systemized. But most felt it was another form of suppression and control by those attempting to dominate them. This led to the training and propagation of the martial systems to secretly go underground. Soon, the Burmese turned against the brutality of the Japanese occupiers and made their way into the arms of the Allied Forces.

The Allied victory and Myanmar’s eventual independence brought hope back to the people of Myanmar, and the indigenous traditions slowly began to come back into public view.

The post-World War II revival of Lethwei was spearheaded by the popular Western boxer Tiger Ba Nyein, who competed in the 1952 Summer Olympics. He was originally trained in British boxing and was able to cross-fertilize Lethwei with modern boxing tactics, much like what had been done in previous decades with Muay Thai — though Lethwei remained staunchly bareknuckle. Tiger Ba Nyein organized and sponsored a more uniform set of modern rules and regulations for Lethwei, which he spread throughout the country. The goal was to restore Lethwei to a modern national sport and an integral part of the burgeoning physical education programs.

All the encouraging and pioneering efforts to help bring Lethwei back to prominence came crashing down as the sport again slid into near obscurity after 1962, when a brutal military dictatorship took control of the country.

Lethwei survived once again due to the efforts of the rural communities, who continued to include it in all their holiday celebrations. Promoters struggled to maintain main-card events in Yangon, including some big-event 15-round Lethwei matches, which drew huge crowds, attempting to mirror the colossal boxing matches of the day during the 1970s in the West.

In the late ‘90s, the Golden Belt Championships attempted to bring back an exciting tournament with modified rules, which became the template for Modern Lethwei. However, the Championships only managed to hold six events between 1996-2010.

The process of key reforms made by the military-backed government began after the long military rule that had lasted from 1962-2010 ended with an election held in 2010.

Since 2011, the opening of the country provided many critical elements that helped aid the growth of the sport, as well as the business sectors. This gave rise to Lethwei as a potential commodity to exploit on a global scale, aided by major events all through Myanmar and in countries like Singapore and Japan, with TV coverage by major European outlets extending the scope and reach of the sport.

To many of us (and to most Thai sports fans), the annual Myanmar (Burma) vs. Thailand fight cards are where we first saw Lethwei in action, either live or on the popular TV broadcasts.

The Thai/Burmese bound-fist contests have been held for decades. Alex Tsui feels the beginning of these type of contests could have started in 1922:

“The conflict between Muay Thai and Lethwei, as far as one could discover, began in the 20th century, at Suan Kularb’s Wild Tiger boxing program, on May 13, 1922, when Burmese boxer An Zaw fought Siamese Karn Libngamlert to a draw after three rounds, in old-style classical Siamese boxing…In the subsequent Suan Sanuk period, Burmese had fought Thai stars, but, with very few exceptions, were always beaten.”

In their popular 1969 book, Asian Fighting Arts, the late Donn F. Draeger and the late Robert W. Smith briefly discussed the earlier contests:

“In the late 1950s, Burma challenged Thailand to a match. A 15-man Thai team went to Burma but refused to fight because of the superior [body] weights of the Burmese. A few Burmese teams have fought under Thai rules and weight restrictions in Thailand with mixed success.”

Generally, the Burmese are bigger and heavier and have a formidable 175 lbs (and above) weight class. The Muay Thai fighters go to middleweight (160 lbs) and that class has grown only in recent times. The Burmese frequently use small-time minor Thai promoters to recruit their Thai opponents, and they generally choose older belted fighters who haven’t fought for a while or have ballooned in weight to make up the higher weight classes (165-180 lbs). This, plus the pay scale, is not enough at the moment — nor has it been in the past — to attract the better fighters. It is also one of the reasons a large number of foreigners were pulled in who could make up all the weight categories, and who could fight at a lower pay scale for a chance at a belt or against a prestige Burmese fighter in Yangon.

The late Kru Nainong was a tough old-timer whom I met in 1993, when he used to visit our Muay Thai training camp in the evening. He competed in a Burma vs. Thailand show in 1960, after witnessing one live with his father (who was also a fighter) the previous year. The weathered photo he brought was his only memento of the fight, and it showed two banged-up fighters hugging each other after the contest. Kru Nainong explained that the Burmese fighter started fast and attacked with the customary explosive bull-rush. He needed to maintain distance because the sudden rush might end with a headbutt. Eventually, he was able to control the inside clinch and deliver enough knees to slow down his opponent before taking control and ending the fight with a high round-kick (his favorite weapon) — but not without absorbing an enormous amount of punishment in the process.

This was a good period for Lethwei, but it didn’t last long, as the political situation within the country again turned ugly, and many of the major shows were halted — although Kru Nainong said smaller ones still ran sporadically in the north during the holidays.

The late Hardy Stockman, author of Muay Thai: The Art of Siamese Unarmed Combat, one of the earliest published books on the sport from 1976, mentions the contests:

“…the Burmese have fought with Muay Thai teams frequently until 15 years ago, when, due to political reasons, these contests were suddenly discontinued. Burmese boxing, a very tough fighting style, is not identical with Muay Thai but does have similarities. Records of matches held after World War II show a more-or-less even score.”

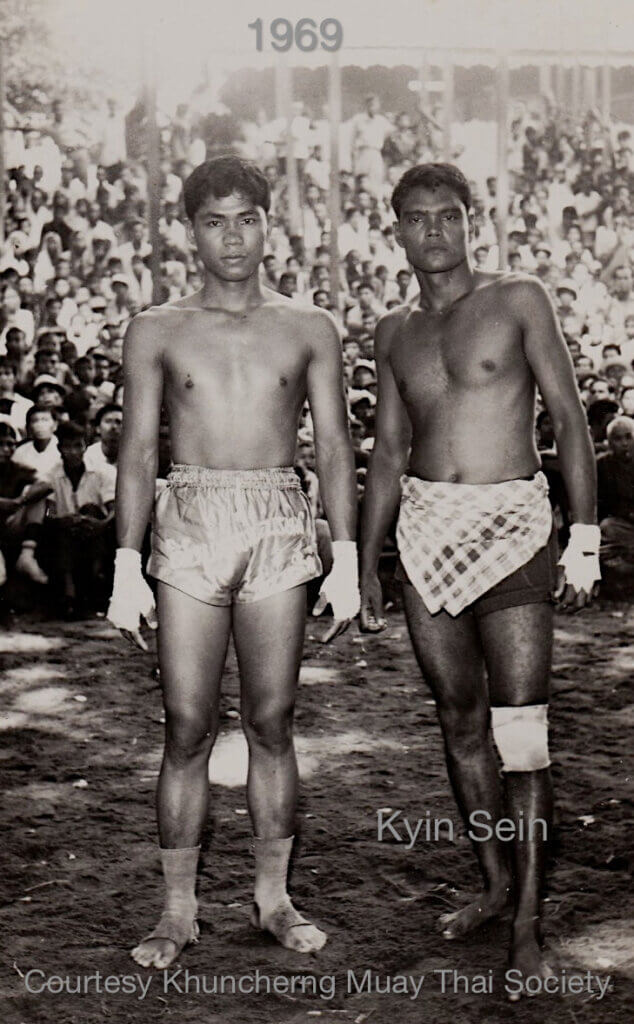

Alex Tsui reported that a Myanmar vs. Thailand bout occurred in 1969 in Kawthoung, Myanmar between a Thai Boxer and Myanmar lightweight champion Kyin Sein. The match ended in a draw. So maybe more bouts were happening on Myanmar soil than in Thailand during the lull in the major yearly cards.

I believe by the mid-1980s (and definitely by 1989, when I began collecting the tapes and watching them), the events were back on and drawing big cheering crowds of Thai and Burmese.

Hardy Stockman, a former editor of the Bangkok Post, was my mentor during my research and training in Thailand. He told me that the record he talked about in his book was a relatively close 60-40 split in favor of the Thais. I believe that from 1990 on, it was closer to 70-30 in favor of the Thais. This could also be because the Thais were coming off their golden era, and the Burmese were still struggling with military control and oppression of the sport. The numbers obviously don’t account for the numerous draws that often occur when there is no definitive winner.

Alex Tsui during the 1998 Songkran holiday documented the fact that during the six days of fighting from April 11-16 that 50 bouts were fought. The Thais won 32 by KO or TKO and Myanmar won 17. There was only one draw.

I personally went up to the North several times to attend the shows. Five fighters whom I know and trained with also fought: Two were from my Thai bare-knuckle training camp, and three were from my Kai Muay. Four won, and one lost due to late notice and improper conditioning. The Burmese opponent felt him waning in the second round and quickly pounced on him.

Mae Sot is a district in western Thailand that shares a border with Myanmar to the west. It is notable both as a trade hub and for its substantial population of Burmese migrants and refugees. The town is part of the larger Tak Province and is the main gateway between Thailand and Myanmar, linked by the Friendship Bridge. As a result, it has gained notoriety as being a “wild West” town for its trade in gems and teak, as well as black-market services, such as human trafficking and drugs.

It is in this small border town that the annual Myanmar vs Thailand televised contest occurs. The fights are held during the New Year Water Festival (called “Songkran” in Thai and “Thingyan” in Burmese). It is a three-day festival that happens during the middle of April as part of a cleansing ritual to welcome in the New Year. During this time, since the ancient days, fighting has been part of the celebrations.

The days leading up to the festival holiday, one can see many glimpses of Northern Thai or Lanna culture and activities from beauty pageants, music and dancing to regular Muay Thai fight cards held at night bazaars to showcase the many local fighters.

The Burmese in the modern era would like the audience to believe that the Myanmar vs. Thailand contests that are being held in Myanmar are new, but nothing is farther from the truth. They have gone on for a very long time.

Burma vs Thailand 1992

Burma vs. Thailand 2001

Burma vs. Thailand 2011

The Thai contest also fully accommodates Lethwei rules and fighters: two referees (one Burmese and one Thai); full bound-fist rules, including headbutts and throws; hand wraps instead of gloves; and no judges’ decisions (i.e., you defeat the opponent, or the fight ends in a draw). The competitors on the Thai side are generally bottom-rung Muay Thai fighters with relatively no bare-knuckle experience, looking to make some money. The Burmese fighters come across the Friendship Bridge from surrounding areas close to the Thai border. Some travel long distances for a chance to earn some much-needed money before returning home, usually the same day.

Concurrently, closer to the river in a forest clearing, smaller makeshift rings are erected for non-televised Myanmar vs. Thailand fights. These fights are more dangerous and are the province of wild promoters and gamblers. You will see many children and less-skilled fighters taking part, often getting hurt or seriously injured in the fights due to their lack of skill and preparation. There is no medical care, and the fighter is on his own once he leaves the ring. Some of the fighters who are unable to get a bout in the big televised fight card wind up fighting in these events for a tiny purse, just to make whatever money they can before returning back home to Myanmar.

The fights themselves are wild brutal affairs. The bouts can only be won decisively by knockout, forfeit, or stoppage (possibly from cuts or exhaustion), like in any traditional Muay Kaad Chuek competition. Each bout is five rounds with two referees, but in recent cards, sometimes there will only be one referee to control the action.

The crowds that flood the area are divided into the Burmese contingent (who mostly crossed the border) and refugees living in Mae Sot on one side of the ring, and the Thai crowd (who come to cheer on the Thai fighters) on the other side. The intensity is palpable, as the nationalistic pride and spillover animosity from the past tend to fuel a lively response every time a favored fighter scores a clean blow or notches a victory.

Thai TV also developed other contests, like the M-150 Challenge in June 2000, which followed the April 2000 Myanmar vs Thailand event. The exciting M-150 Challenge matches were an attempt to use a modified bare-knuckle format that featured a wider cross-section of fighters from Cambodia, Laos, Japan, Thailand, and Burma competing against one another in a round-robin style tournament. There was only one referee, and the fights had judges and point decisions. The winner received a belt, a trophy, and a hefty purse.

The purpose of the fights is to honor a rivalry that goes back to ancient times. They are celebratory in nature and tend not to foster any further animosity between the two countries.

In recent years, Myanmar has hosted their own events with Thai fighters, and the Burmese fighters have done well. They have boasted Lethwei as an art of nine weapons and proposed that it is deadlier, more brutal, and older than Muay Thai in a dull campaign. No one seems to understand that the older bare-knuckle form, moving into Muay Kad Chuek, contains everything that Lethwei has in its arsenal and is as old as Lethwei as we have shown.

Nine weapons were in all the traditional ancient arts of Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos. Nine is not only the action of the head but also symbolizes the theories and strategies that one uses to fight in the older Thai martial arts. There are also major and minor weapons, like using the forearms, shoulders, fingers, and feet, same as with the old traditional Thai and Khmer bare-knuckle/bound-fist arts. As a new sport, Muay Thai was stripped down to the Art of Eight Weapons. When one compares Lethwei to a Thai art, it is comparable to bareknuckle/bound-fist arts that have various regional systems. Modern Muay Thai has evolved from the ancient past. It has developed into a durable, formidable ring art that has also innovated a way for the art to be taught in camps and with training tools that are specific to its development. This innovation seems to be lost on those in Lethwei, who are now using those very tools and architectures to rebuild their sport into a modern competitive one. In understanding the current evolution of modern Lethwei, one can see that the construction of the new model is clearly built on modern Muay Thai, including decision victories in some promotions.

Muay Thai is adaptable and fluid, fits into the modern MMA world, and has been easily adapted in the past to fit into both Japanese and Dutch ring-fighting systems. Even without headbutt training, the Thais have a solid clinch game to deal with it most of the time. They generally don’t do any special training when fighting the Burmese, and I have noticed that they can handle the clinch/headbutt attacks — unless they get caught, which happens. There are decades of Myanmar vs. Thailand bouts to back this up. If a Thai fighter needs to change or add the headbutt, they can easily do so, just as they can adapt easily without any special training to fighting without gloves, even though they are not trained to fight that way.

The Thais also understand that the Burmese are raw unpredictable fighters who are slowly coming into their own, with a strong desire to win. The Burmese have attempted to capitalize on tools like the headbutt and fighting with just gauze-wrapped hands, both of which have been eliminated from many fighting sports. Whether they will dominate and collect a strong number of wins with these tools once their opponents learn and close their defenses to them remains to be seen.

Lethwei retains the rugged durability and toughness of the ancient bound-fist fighting ways. It is a part of the past that the Thais have let go of — in part to move forward into a more modern fighting sport that has proven itself throughout the world.

All the past tensions, battles, animosities, and victories are commemorated each year in the annual Myanmar vs. Thailand contests. The battles will become even more exciting as Lethwei grows and expands with fiscal support and increased opportunity. It deserves to fight for its place as one of the world’s toughest sports.

Born to Battle Notes:

- Lethwei has had problems advancing and developing the sport over time through a long stop-and-start process. Since the opening of the country, Lethwei has evolved from a template born from the first Golden Belt Championship fights in 1996. I call this variation “Modern Lethwei”, as they push for more safety and rules and use decisions to name a winner to draw more foreign participation. I believe Myanmar has the rare opportunity to keep Lethwei moving on two different fronts. The big organizations can continue to help maintain the cultural roots of the sport as it develops into a newer tradition that can be fought throughout the world. For example, if the newer promoters show that they can support the rural communities by offering cash incentives, promotions, and maybe special events in which local fighters can rise to the mainstage from these local communities, then we can have the best of both worlds. The promoters will able to demonstrate that they care about the core root level of Lethwei, while elevating the sport through new rules and regulations for safety in formats that can be used and broadcasted throughout the world. I believe it’s crucial to keep the old events alive, while moving the sport forward into modern times.

- It is not my purpose to reduce the debt owed to or the influence of ancient Khmer/Cambodia martial arts culture on the region. Rather, I am illustrating how the same pattern of different cultures claiming to have developed modern Ring Muay Thai remains hollow without a deeper understanding of how long it took the Thais to develop and evolve into what we see today in the ring. Here, we are focused primarily on the histories of Myanmar (Burma) and Thailand. This is simply to show how close the claim is to what the Burmese are now saying.

- I have seen on television (or through digital or video) or have been in person at many of the Burma vs. Thailand events during Songkran/Thingyan from 1989 through 2019. I arbitrarily picked older (1992, 2001, and 2011) videos to illustrate how the live shows were done, and what the results were over a period of 19 years. It was also a matter of the condition of the original copies that were transferred from VHS tapes/VCD to digital. The quality of some of the shows is not as pristine, and thus not as enjoyable to view online.

- The M-150 Challenge match from June 2000 was one of several shows that attempted to build on the popular Burma vs. Thailand events in Thailand. This particular show used more Burmese than Thais in the opening round-robin:

- Cambodia (red) vs. Burma (blue)

- Laos (red) vs. Burma (blue)

- Japan (red) vs. Burma (blue)

- Thai (red) vs. Burma (blue)

- Thai (red) vs. Burma (blue)

- Noted scholar Peter Vail’s work is best consulted on matters of Muai/Muai Thai, as well as its meaning and significance in Thai culture. His outstanding research should be supported and read by everyone interested in this topic:

- Modern Muay Thai Mythology

- Muay Thai: Inventing Tradition for a National Symbol

- The research of Ajarn Alex Tsui of the Khuncherng MuayThai Society began in 1966, and he has continued training, building, translating, and compiling records that will eventually form several volumes on the topic of Muay Thai. He was one of the first foreigners to be honored as a special guest referee during a 3-day Lethwei event in Mawlamyine in 1998.

- Born to Battle: Burma vs. Thailand is a short documentary that was originally created as a special Vanishing Flame release. It was updated for inclusion on both the special and deluxe editions of Born Warriors.

- Lekka Moun Khat is a short piece that can be found in the bonus material on the Born Warriors Redux: Bound Warriors solo disk and is also included on both the special and deluxe editions of Born Warriors. It introduces the ties between the ancient arts of India and Mongolia, and those of Myanmar. The unreleased Footprints in the River, which focuses on Burmese martial arts, also investigates this topic, specifically through Thaing, Naban, and Lethwei.

- I feel it was and continues to be vitally important to save what we can from the older traditions in Southeast Asia and India. It was important to me personally to learn every single technique to preserve them. I translated many old handwritten manuscripts and, in some instances when there were none, I created one with my teacher, so we could preserve what was originally taught. The arts became popular much later, and even then, since the arts were largely forgotten, the newer teachers leaned mostly on recreation.

- When I refer to ancient Muay (or Muai) or ancient bareknuckle/bound-fist techniques, specifically for Thailand, I am not referring to modern Muay Boran, which is a form created much like Wu Shu or Tae Kwon Do to sell to the world and general public. I am referring to the original surviving methods.

- In his book Burmese Bando Boxing, Saya Maung Gyi, Ph.D. mentions three other known Burmese fighters who competed in early Myanmar vs. Thailand matches. One of whom was Mein Sa from Tavoy, who was reported to be an expert in grappling and elbow techniques. He fought mostly in the towns and cities of southern Burma. The second was Thara Saw Ni, who was a Karen (Kayin) Lethwei competitor known for his deception, headbutts, and foot techniques. It was said that he was older (in his 40s) but fought against many younger fighters. Most of his bouts were held among the Karen people in Burma and Thailand. The most popular of the three is Po Thit, who, prior to 1940, went to Thailand and fought in Chiang Mai, Cheng Rai, and later in Bangkok and other cities. He is mentioned briefly by Draeger and Smith in Asian Fighting Arts, and again by Alex Tsui:

“Po Thit was very strong fighter who beat quite a few Thais in the North until he was battered by the famous knee assassin Wan Muangchand on June 15, 1932, in Chiang Mai. It was a rather gruesome affair, with the Burmese champion cut up badly by elbows, and the Thai — though the winner — had to be treated in the hospital after the fight for the rough headbutts he took on his chest and body throughout the bout.”

It is said that Po Thit remained in Thailand to teach, but no records of his students or where he taught have been uncovered so far.

© 2019, Vincent Giordano. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without the express and written permission from the author is strictly prohibited.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.