by Vincent Giordano

The origin of this important early film footage begins with the career of Jean Alexandre Louis Promio, who later became known as Alexandre Promio. He was a pioneering French cinematographer, who filmed the footage in July 1896. Promio was an assistant to a French optician when he witnessed the first presentation of the Lumiere brothers cinematographe, a motion-picture apparatus used as both a camera and projector in June 1895. The Lumiere brothers were among the first filmmakers in history, and the burgeoning technology greatly excited and impressed Promio. In March 1896, he left his job to start working with the Lumiere brothers, who were looking to expand their business worldwide. After a short time, Promio — along with M. Perrigot, who taught Promio and others how to use the cinematographe — became responsible for training the first generation of cinematographe operators, who exhibited and showcased this new invention worldwide.

As one of the original 17 film operators, Promio traveled extensively to several countries from April 1896 until September 1897, holding exhibitions to demonstrate and introduce the new technology to the public, and to photograph local scenes that would greatly enhance and expand the growing Lumiere film catalog.

In July 1896, at Sydenham Crystal Palace Park in Hyde Park, London, while he was demonstrating the cinematograph to the public, Promio shot 11 films about the Regent Park Zoo landmarks, daily affairs, Princess Maud’s wedding ceremony, and three films which were suspected to be a representation of the people of the Dutch East Indies: Danse Javanaise (Lumiere catalog #30), featuring four women dancers; Jongleur Javanais (Lumiere catalog #53), focusing on a solo performance of ball exercises; and Lutteurs Javanais (Lumiere catalog #56), showing two men lightly sparring.

Like most of the Lumiere clips at the time, each running between 40-55 seconds long, Jongleur Javanais, Danse Javanise, and Lutteurs Javanais were recorded in a single take in an open field, with images of trees and many of the same participants in the background.

The actual origin of the performers in the clip, as well as what was being performed, was initially confusing. In a race to capture anything they could film that would demonstrate something exotic or rare to the hungry public at the time, it seems the cameramen like Promio might have been careless, confused, or uncertain about the true origin of the performers they were filming and just labeled what they thought they were without conducting the proper research.

In a footnote provided by the Victorian & Edwardian Martial and Exercise Films Channel page, they attempt to clear up some of the confusing name changes that further clouded understanding of what the clips actually represented:

“In the 1897 Catalogue of Lumière Cinematograph Film published by Fuerst Brothers, the company’s London agents lists films (53) ‘Japanese Jugglers’ and (56) ‘Japanese Wrestlers’. In the 1907 Catalogue Général des Films Lumière, their nationality was changed to Javanese.

In the summer of 1896, a company of exotic performers were one of the attractions at the Crystal Palace, and they were from Burma. These performers are the ones that appear in Lumiere films 53 and 56. Therefore, it seems clearly that their nationality is Burmese and not Javanese.

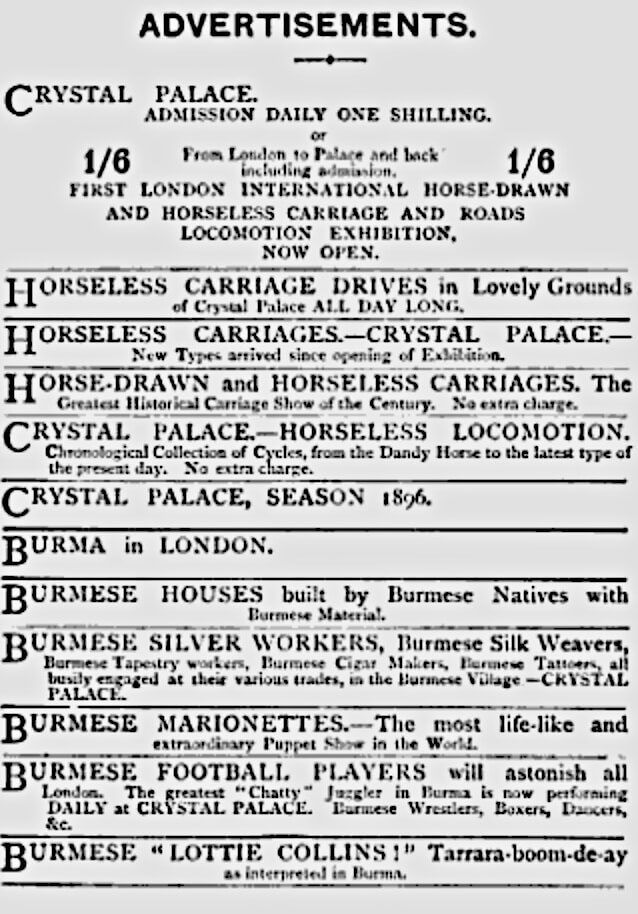

As advertisements in the Morning Post dated 21 May 1896 showed, dancers and wrestlers were among the ‘Burma in London’ attractions. The Burmese ‘football players’ also mentioned in the ads of the Morning Post are in fact Chinlone practitioners, an ancient Myanmar (Burmese) ball art based on traditional dance and martial arts movements.

Chinlone can be played as a team sport, which probably gave rise to billing it as football. But when performed solo, it resembles a juggling act using balls.

One of most famous practitioners [of juggling] … was Moung Toon. It is most likely that we are viewing a performance by Toon in film #53.”

The Lutteurs Clip #56 begins with the two fighters circling, one clapping his hands to draw the opponent. They strike lightly with open-handed slaps. It’s clear from either a Naban (wrestling) or Lethwei (bare-knuckle fighting) standpoint that this is not an actual fight, but a light demonstration for the audience. There is musical accompaniment, which is standard for both fighting arts. Since we know this was shot in England and not in Burma (Myanmar), the group is obviously a traveling troupe, presenting a demonstration of Burmese culture through music, dance, and sport.

This description of a Lethwei (Burmese boxing) match from a written account of the time gives us an eyewitness viewpoint. This excerpt from “Among the Burmese”, taken from The Living Age, Volume CXXXVIII circa July, August, and September 1878 mirrors closely what we are seeing here — especially at the beginning of the demonstration:

“…two combatants presently stand forth, prepared for the fight. Tall but muscular of limb and swarthy almost to blackness, their clothing consists only of a tightly bound waistcloth. The hands are bare, but instead of clenched fists, the open palm is the only weapon of attack … other movements follow, expressive of the fiercest hatred and haughtiest contempt, and one or the other probably leaps into the air to show off his superior strength and agility.”

It is odd that this British writer witnesses a Lethwei match with no clenched-fist blows – or he is possibly watching a Naban match where slaps would be more fairly common? I chose this quote because of the time period in which it was written, and how close his description was to what we we’re witnessing during this exhibition. One other quote might provide more insight:

“The fight continues in the same fashion for a considerable time, but no serious injury is inflicted, and the presence of the local police under English superintendence is enough to prevent any undue excitement or breach of the peace.”

This follows what we know about British control of the sport, in terms of what was allowed to be displayed in public gatherings. In the chapter “Traditional Burmese Boxing” from We the Burmese: Voices from Burma by Helen G. Trager, we see a clear demonstration of this:

“After Burma was annexed by the British, Burmese Boxing suffered a decline. From being the foremost sport of the elite warriors, it became merely one of the attractions at an out-of-the-way pagoda festival. Burmese boxers were classed with vagrants and habitual offenders under Sections 109 and 110 of the Code of Criminal Procedure. Burmese Boxing almost died out in Upper Burma. The traditional art was kept alive in the paddy fields and villages far from the former royal capital of Mandalay.”

I believe the British account we are reading could possibly be just a celebratory Lethwei match, but nonetheless, it offers insights into what a performance of Lethwei would be like during this period.

The slapping (or “slap boxing”) is a training regimen designed to train the fighter to develop fighting skills, and since it is a bareknuckle art, this was their method of sparring. It was also a safer way to demonstrate the art without anyone getting hurt.

This would be true of Naban or Lethwei and reminds us that this clip is much more of a light exhibition, rather than a true, grueling, full-rules match. When viewing older footage or photographs to decipher what is actually happening, people are often confused. Few people train in the older forms of these arts, so slap boxing might not be something they have ever seen or practiced.

The second half of the clip involves one fighter moving in for a takedown, with his opponent fighting him off by holding onto his waistcloth belt until finally being brought to the ground. The fight continues on the ground, with the top fighter being bridged off with the use of a leg and upper-body arm movement. The fight resumes on the feet, with the fighter who has been the aggressor through most of the match grabbing his opponent’s leg and forcing him to the ground. He circles, monitoring the position of his downed opponent’s head, then releases as the opponent rises to his feet. The fight continues on their feet until the footage abruptly ends.

After viewing the footage for the first time, I leaned more toward the clip being of Lethwei, but it became clear in how the slaps and movements led the fighters to the ground — and especially how the groundwork was handled — that it was indeed Naban. Lethwei used throws, trips, and holds that could lead to slamming the opponent to the ground and landing on him with knees and elbows, but the ground isn’t where they wanted to stay. In the same way, Naban used strikes, along with throws, trips, and holds to bring the fighter to the ground, where they could pin the opponent or apply finishing holds and locks. Any part of the body was a legal target. This is why my feelings in the end leaned heavily toward this being Naban.

The late Saya U Bo Dway of the Mandalay Research Center shared with me that some skilled fighters would often fight in both Naban and Lethwei matches, since some tournaments held Naban matches before the Lethwei main card. Evidently, there were some crossovers with fighters who could do both with a high level of skill.

Naban is one of the oldest practiced martial arts systems of ancient Myanmar. It is a term used to encompass the diverse grappling methods within the country, both ancient and modern.

During the early years of its development, the Naban system was influenced by the wrestling systems of ancient India, Mongolia, and Tibet. The influences varied based on region, but most point to the older, dominant Indian styles of wrestling — like Mallayuddha, the ancestor of Kushti — as a major root.

In S.H. Deshpande, Ph.D.’s book, Physical Education in Ancient India, many of the early writings on the evolution and sport of wrestling are described in detail:

“Mallayuddha or Malla Vinoda (Wrestling): Wrestling was one of the most popular sports of ancient India … it was also part of war training. People resorted to wrestling for two major objectives. Firstly, it was an art of self-defense, and secondly, [it was] a means of subsistence … wrestling tournaments were held in the form of festivals … Bahuyuddha – a type of wrestling was included in the study of Dhanurveda, as one of the modes of fighting in battle.”

The older, ancient model of Naban could have also been influenced by the rougher and deadlier sports like Bahuyuddha (freestyle wrestling), with its free-flowing integration of striking, along with grappling:

“It was almost a free fight, with no hard-and-fast rules. The wrestlers (or the contestants) who engaged in Bahuyuddha were freely using the following tricks that were otherwise banned in competitive wrestling:

- Pulling of hair

- Injuring the opponent with nails and teeth

- Slapping the opponent with open palms

- Use of fist strokes

- Kicking and striking with knees

The motive of such type[s] of wrestling was not only sporting, but also fighting and killing. Even in Bahuyuddha, the wrestlers used to exhibit high skills of wrestling: Various holds and their counter holds, swift movements, tremendous force, and application of strength were some of the characteristics of the bout.”

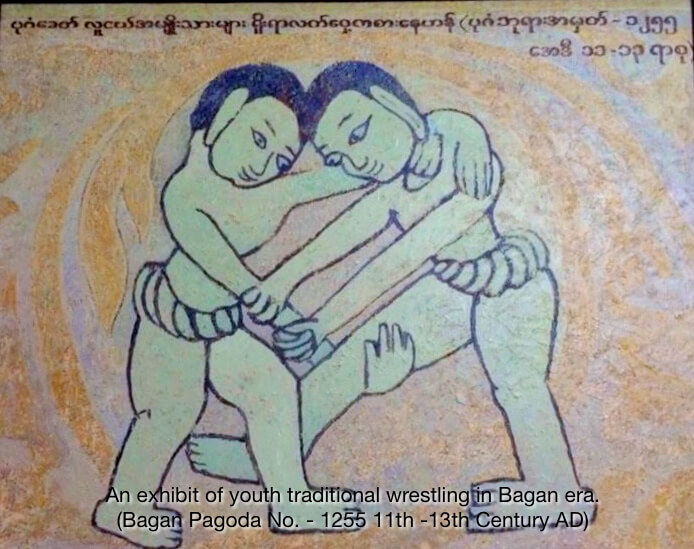

Naban in modern Myanmar has been all but forgotten. It lives on in the rural communities, much like Lethwei did to keep the sport alive during its long suppression before its slow revival in the modern era. To keep Lethwei in the forefront, Lethwei promoters used ancient Bagan murals to illustrate the ancient origins of their sport — even though some are, in fact, ancient paintings of Naban.

Naban is still an active part of the Chin ethnic festivals. The sport is called “Lai Paih”, and Hnairlawn (a village close to the capital) is where many of the best wrestlers are from. This traditional form of wrestling is exclusively practiced by Chin men and represents a chance to demonstrate one’s masculinity and strength to the community at large. The Chin State is located in the southern part of northwestern Myanmar, bordered by Bangladesh and India to the west, and the influences of India are mixed with other sources. The Chin favor an ancient form of belt wrestling that involves aiming to knock the opponent off-balance and throw the opponent to the ground by gripping a belt tied around the wrestler’s waist.

In the Shan state, which borders China to the north, they are said to practice Chinese-influenced forms of grappling. However, they may have been integrated into their indigenous forms of Thaing over time or may not be practiced as much in modern times.

The Rakhine State (formerly known as “Arakan State”) is a coastal region of Western Myanmar that is home to Kyin wrestling, which is one of the ancient sports of the Rakhine people. This form of Naban supposedly derives from the ancient form of Mallayuddha, which was later combined with Iranian and Mongolian wrestling to become the unique form of wrestling we see today.

Naban was popular with Karen (or Kayin) as well as the Kachin people. They were once strong competitors, although the sport has seemed to wane in popularity in those communities. The Karen and the Mon focused on Lethwei — even when the sport was at its lowest point. They were the strongest supporters of the bareknuckle art.

This unique, short glimpse into the past demonstrates that martial art forms evolve over time, usually after having to overcome various forms of suppression and control that might, at times, render them extinct. In Myanmar, the many different ethnic groups survived various old traditions within their culture through festivals and religious celebrations, keeping them alive for future generations.

Lethwei seemed to be a more dominate tradition over the wrestling methods of Naban. The revival of Lethwei in recent years appears to be a positive sign that, at some point, Naban might go through the same sort of revitalization and rebirth.

Notes:

1. The advertising for the Burma in London show did indeed include Burmese wrestlers and boxers. The inclusion of both wrestlers and boxers fails to help us identify clearly and definitively what is in the old film clip. Even though my belief still leans towards it being the older form of Naban; I can also feel the echo of the late Saya U Bo Dway’s description of the earlier time periods, when fighters could fluidly compete in both Naban and Lethwei. Since the show was held over multiple days, it could have been a flashier display of more kicks and punches on one day, and a more integrated striking and grappling display on another. Unfortunately, the reviews I found do not offer any further description of this portion of the show.

The Morning Post(London) 1896

2. Wrestling is one of the oldest traditions in Myanmar, as evidenced by the old wall images of wrestlers in Bagan. Many people felt that because there was wrestling (Naban), there must have also been a form of bare-knuckle boxing (Lethwei) during these early periods. Sadly, Naban has long been forgotten, outside of the few ethnic groups that continue to keep it alive, and so eventually, the bare-knuckle method eclipsed the wrestling method, much like we witnessed in early Thailand, where wrestling as a solo sport never really took hold. Unfortunately, there is still not much interest in preventing the erosion of oral and written traditions, along with these physical techniques and training methods, and so we are losing a great link to the past.

According to author Man Thint Naung, the Karen people might have started practicing Naban before the advent of Lethwei. In time, Lethwei became more emphasized, and Naban bouts often preceded Lethwei ones during the many festivals that occurred during the calendar year. Some of these wrestling techniques were absorbed over time and evolved into the art we see today.

© 2019, Vincent Giordano. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without the express and written permission from the author is strictly prohibited.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.