Zoran Rebac was born in Zagreb, Croatia on March 24, 1954. He began his training in Tae Kwon Do as a teenager, eventually achieving the rank of 2nd Dan. Zoran was a member of the national team and won the National Championship twice before turning his attention to the art of Muay Thai.

After graduating with a degree in physics from the University of Natural Sciences in Zagreb, he took his first trip to Bangkok and began his training in Muay Thai. Zoran trained at the legendary Muangsurin Camp in Bangkok, and the Singprasout camp in Chiang Mai. When he returned home to Croatia, he opened his first Muay Thai gym in Zagreb.

He continued training in Muay Thai and then began devoting time to Lethwei, taking his first trip to Myanmar (Burma) soon after.

Zoran’s deep immersion in Muay Thai and Lethwei stretched over four trips to Thailand and Myanmar between 1982-2000.

His first book, Thai Boxing Dynamite, came out in 1986, and his second book, Traditional Burmese Boxing, followed in 2003. He additionally released a companion video for each book. Even though Zoran is retired from teaching, he continues to advise and mentor his former students, as well as those in need of his advice and training tips.

Zoran still lives in Croatia with his wife and two children.

When did you begin your martial arts training? What was your initial inspiration for training?

I was 16 years old when I first started training. I was very strong, with a lot of energy to burn, but I was also extremely clumsy. I did not know what to do with myself. One day, a close friend came to me with a fantastic story about Tae Kwon Do: the spectacular flying kicks, breaking bricks. It was also the beginning of Tae Kwon Do in former Yugoslavia, so we decided to enroll. There was no internet then, and so I had nothing to do but train.

A few months later, my friend decided to quit, but I stayed and continued working hard. I was one of the first 10 black belts to graduate and later became a member of the national team.

Master Sun Jae Park, who was a Tae Kwon Do master who taught in Rome (Italy) at the time, made a great remark to me about discipline, and how one needs to really take enormous effort to train, refine, and polish one’s techniques. Even today, I follow his advice to train each technique to perfection. The mind is important in this process. You cannot make progress without the mind and body forged together.

In the early 1980s, you decided to travel to Thailand. How did you make this happen?

As a naturally curious person, I was not limited to training only in Tae Kwon Do. I tried training in several other martial arts, like Aikido, as well as attending a few Goju Ryu Karate seminars. I fell deeply in love with the martial arts, as many long-term practitioners do. But at this point, I was growing up in a semi-communist state, so my resources were limited, and my window to the outside world was through James Bond movies.

In The Man with the Golden Gun, there was a short scene shot in a Thai boxing stadium (that I later learned was the famous Rajadamnern stadium), and it impressed me so much. After that, I couldn’t get Muay Thai out of my mind. I became disillusioned after I was eliminated from the national team, even though I had been a champion at the time, so the idea of traveling to Thailand started to grow more and more in my mind.

I was a subscriber to Black Belt magazine, where I found several interesting articles on Muay Thai and Lethwei. The late Hardy Stockman, who authored the first book on Muay Thai, wrote interesting pieces on Muay Thai and Krabi Krabong for the magazine. After I graduated from Zagreb Natural Science University, where I studied physics/geophysics and meteorology, I finally made my first trip to Thailand happen.

What were your early experiences training in Muay Thai like?

So, I find myself in Bangkok. I’m expecting to easily find a Muay Thai camp, and, in a Western way, pay a fee and start my training. I ask around, but nobody can give me an address of a camp or a trainer, so I visited the TAT (Tourism Authority of Thailand) offices. I ask many times, but again, no one can help me. Disappointed, I head for the door — when one of the employees calls out to me, “Wait, wait. I have a friend who is a Thai boxing trainer.” He carefully writes the address on a small piece of paper for the taxi driver, and a note that I want to join their club and train in Muay Thai.

The taxi driver drops me off in front of a restaurant in some remote part of Bangkok. I go inside and show them the paper, and they send a boy out to find the trainer. I order some food and wait for over an hour. Finally, the trainer, Dentharonee Muangsurin, an ex-champion of Rajadamnern stadium, arrives and takes me over to the camp to meet the owner, Mr. Sa Non. They accepted me out of curiosity, as there were not many “farangs” (or foreigners) training full-time in the Muay Thai camps at the time. But soon, they saw my enthusiasm, efforts, and hard work, such as heavy training twice a day, every day, and they took a liking to me.

It was a completely new experience for me. It was my first camp. It was out in the open with a cement floor. Old, heavy bags. The trainees would live at the camp, sleeping and eating there. Some were refugees from Cambodia, and some were Thai boys from the provinces. They never asked me for money. Ever. I was the only member of the camp who slept in a small hotel.

Soon, I faced the hard reality of the training: a lot of bruises, hard training daily, sparring sessions. I was tall, but a few of the Thais were stronger than me, especially in clinching.

I spent all my free time during this visit training. I went up north to Chiang Mai to see about the training and attended some of the rural boxing matches there. I trained there, as well.

I met other legendary Muay Thai figures at the time through the owner of a small hotel I was staying at. I met the late Yodtong Senanan, who was the head of Sidyodtong Muay Thai, one of the biggest camps in Pattaya, and I visited with the legendary fighter and trainer Apidej Sit Hurun at the Fairtex Muay Thai camp.

I must emphasize I was never a professional fighter, due to my job commitment in Zagreb. I was an employee of the Hydro-Meteorological Institute, as well as a weather forecaster on national television. All this helped me popularize the sport. I wrote articles for several newspapers and created a few short television documentaries about Thailand and Muay Thai. This, in addition to my teaching, helped promote Muay Thai in my home country and abroad.

What was your first trip to Myanmar (Burma) like? How hard was it to find a teacher or a place to train?

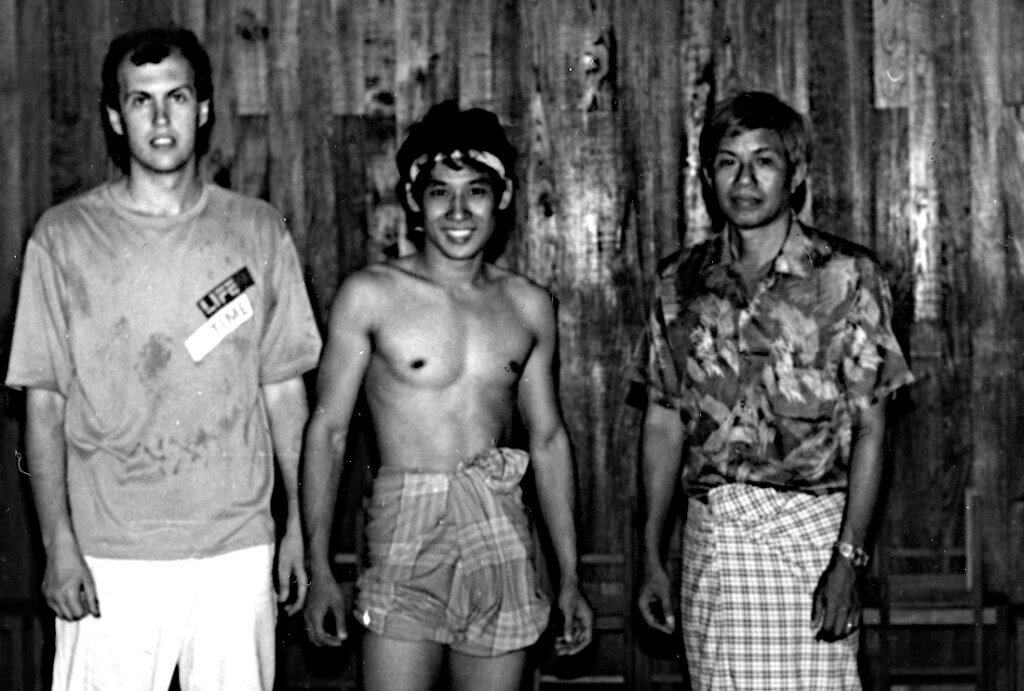

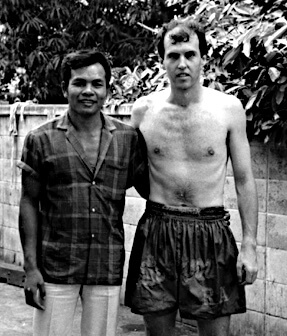

In my second or third trip to Thailand, I decided to visit Burma and study the differences between Burmese and Thai boxing. So, again I found myself in Yangon, in a cheap hotel, desperately looking for a camp without much success. But by luck and strange coincidence, I happened into a small coffee shop to have a Burmese yogurt drink. To my great surprise, I noticed a large Burmese boxing photo on the wall. I quickly asked, “Who is this? Where is this club?” It was, in fact, Nilar Win’s coffee shop, which was run by his family. And again, I found myself training. Nilar was a Yangon junior champion at the time. A fantastic technician, very brave and strong, but with a calm demeanor. The gym? It was basic: no dressing room, no showers, and very hot. Actually, very similar to the gyms where I trained in Thailand. The surface was an old canvas with sawdust under it. But with my previous knowledge and experience in Muay Thai, I easily adjusted.

Did you train with any other teachers during your stay?

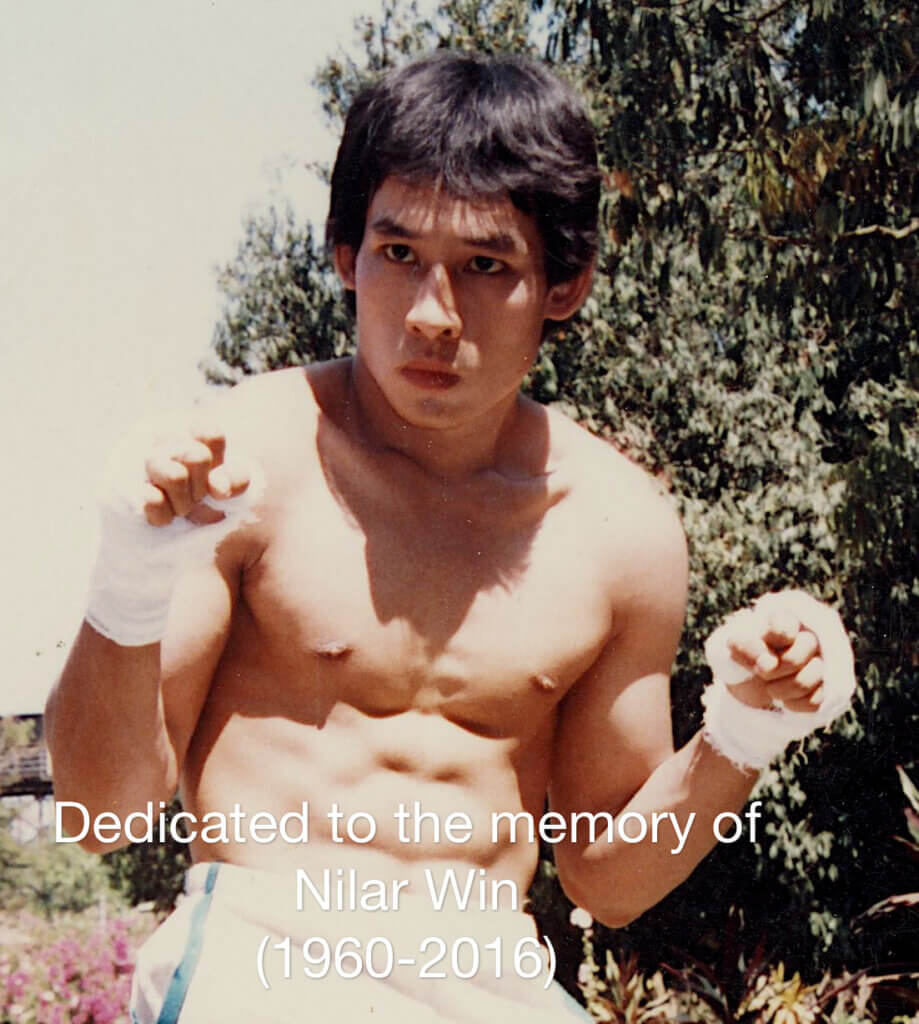

I trained primarily with Nilar Win and Thaung Nyunt in Yangon, but I visited a few other clubs in Bagan, as well as Yangon. I put all the information I collected into my book. But after some time, Nilar and I became very close friends, more like brothers. When he left Burma, he stayed with me for a few months in my home in Zagreb, and together, we ran what was possibly the first club in Europe focused on both Thai and Burmese boxing. After this, Nilar received a visa for France, as there is a Bando and Lethwei Federation there, established by Jean Roger Calliere and Suso Vazquez Rivera. He continued to teach in Paris until his untimely death in 2016.

What were your first impressions of Lethwei, having already trained in Muay Thai?

The basics are similar to Muay Thai, but there are a lot of differences with the elbows, knees, and especially the headbutting. The fighting tactics are much different, with more aggression and bare-hand combinations. Mostly, training was seasonal — contrary to the present, with camps operating full-time throughout the year, like in Thailand.

What was your experience like with the actual tournaments?

Here, I must explain that at the time, Burmese traditional boxing was a seasonal sport. The fighting events were organized in the provinces during the rice harvest season. There was not, in my opinion, any specific method or systemization of gradual learning (like in Tae Kwon Do or Karate). Youngsters just enter and train everything. There are even fighters who just train themselves and enter the fights. Every bruise is a lesson. Every defeat is a school. My own personal feeling is that the rules were very cruel. After three rounds, the fourth round is unlimited, until one of the opponents is either knocked out or gives up. There are no weight categories, and there are two referees in the ring, who often have a hard time controlling the match. If an opponent cannot stop the bleeding from a cut, he loses the match. I was surprised that with such rules in place, there were not more serious injuries.

You photographed many events for your work. How hard was it to film and do your research during the years you were there?

I’ll illustrate this with a funny story. We decided to go to one tournament in some far-off district in Yangon. Nilar tells me he can’t go, but about 10 or so of his boys from his club will take me. So, we go by truck; I have a “first-class” seat close to the driver in the front for the long drive. When we arrive, the arena has a big roof made of palm leaves, and the ring is lit by a few dim fluorescent lights. There are no seats. You sit on the ground on some knitted leaves.

In the middle of the fight, a minor quarrel breaks out close to me, and within a few seconds, almost all of the stadium erupts into one big, bare-knuckle brawl. I quickly cover my camera, and my friends surround me, protecting me from the melee. Soon, the police arrive with long, black, heavy sticks, which I remember to this day. They then move through the crowd, demanding that everyone sit down, and those who refuse are struck heavily with the sticks. To this day, I can still hear the sound of the strikes over the backs of some of the people close to me. Everyone got back to their seated positions, and the fights continued like nothing ever happened!

Can you share your feelings about the difference between these Lethwei shows and the Muay Thai ones in Thailand?

They are very different. Muay Thai is commercialized. There are promoters, newspapers, TV channels, magazines, and heavy betting. Its popularity is huge in Thailand. Burmese boxers received small amounts of money for their efforts. They fought mostly for glory or just for fun. If they won the rural tournaments, they would receive a triangular flag, like a trophy. They did a boxing dance at the beginning, and again at the end, if they won. The audience would roar their approval for those they liked. In the end, they gained popularity in their village or district, and pride in themselves.

Lethwei has only evolved in the last decade or so. Have you followed its growth? And what are your feelings about the future of Lethwei?

I really don’t know. You are aware that old Thai boxing (Muay Boran), as well as Burmese traditional boxing (Lethwei) are ancient sports, and I have often compared the fighters to gladiators in my work. It was a tough life, with very little financial reward. At least fighters in Burma and Thailand were deeply religious people with respect for each other. In Burma, villagers knew how to cultivate the land and were used to hard work every day. They fought to celebrate their crops and harvest.

I now see many foreigners from Europe, Japan, Australia, Canada, and the USA competing in Lethwei. It’s the same problem for a professional fighter today. What will happen after their fighting career is over? The pay scale is still not enough for most of them.

Much of this has happened before in Thailand. The rules have changed; the influx of TV/media, businessmen and promoters, the hope of bigger and bigger prizes. Even the methods and techniques have changed: a new format, with some tournaments having decision victories, and one referee. They no longer fight the exhausting fourth round. It’s a new version of Lethwei. But every sport must evolve. If it will grow or not remains to be seen.

In the end, every person must find their own way. You strive to become a better person. For me, my way is to continue studying, training, and learning how to use my mind and body to the fullest extent.

What is happening with you now, personally and professionally?

I am not teaching anymore but still practice, mostly for fun and health. If someone reaches out to me for help or recommendations, then I might agree to teach them, advise them on tactics, methods of training, discovering weak and strong points, whatever is needed.

I am mostly focused on my family and other obligations. I am looking to find a new publisher for my books and DVD. When time permits, I would like to complete my documentary on Thaing (Burmese martial arts). I have a lot of valuable material. I see myself possibly creating a special YouTube channel, but it’s all time-dependent right now on what gets done or not.

© 2020 Vincent Giordano. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without the express written permission from the author is strictly prohibited.

End Notes:

The English version of his book, Traditional Burmese Boxing, from 2003 is a translation of the original 1987 book that he released in his home country. The English version of his first book, Thai Boxing Dynamite, which was released first in 1986, and then again in 1987, was a translation of his original book, released in 1983.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.